Originally Published at Philippine Daily Inquirer. Feb 4, 2002. by Gino Dormiendo

ART CONTESTS have an uncanny way of extracting the best-and, if unchecked, also the worst-from practitioners. For a judge, the task of separating the chaff from the grain can prove awesome. A judge would need to see one particular work singly and also in comparison with other works, and subject it to the most rigorous standards.

In the nationwide Diwa ng Sining art contest, “Expressing Hope Through Art,” at the Art Center, SM Megamall, sponsored by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Rotary Club 3810, a record-setting number of 247 entries in various media vied for the best three prizes and Jurors’ Choice citations, the number of which was left to the judges’ discretion. Participants were required to work on the theme, which they either interpreted too liberally or too literally, to the viewer’s dismay.

It was evident that a number of the participants had a rather limited grasp of the theme, resorting to such hoary cliches of imagery as a plant emerging from the soil, or of infants and children cradled in the arms of their mothers, or of humanity literally rising, phoenix-like, from the face of the earth. Some even submitted basically identical images, with a few variations here and there, which can prove embarrassing when viewed in the same venue.

Some aspired to loftier levels by resorting to symbolical or metaphorical devices, but these don’t guarantee quality. There are, to be sure, pitfalls by omission and commission. Not to mention a slew of other shortcomings ranging from lack of coherence, unity and restraint, considering the strong urge to fill up every square inch of the canvas.

Named as co-winners were “Positive Sign,” a mixed media work by Armando Flaviano, “Boundary Withdrawn,” an oil on canvas by Eugenio Cubillo, and “Happening Ordeal Portions of Ego,” a mixed media by Simoun Quilang.

Flaviano’s entry makes clever use of discards of film negatives as the central image, an allusion to the technological invention that has exposed mankind’s innermost emotions. One needs to look closer and examine the amorphous shadow emerging from the assemblage of recycled film stock, which forms the faint outline of a human being, arms outstretched.

Cubillo’s work is a portrait of the artist in this age of technology contemplating what the computer icons have done to his brush medium. Virtually surrounded by the semiotic onslaught of symbols, the forlorn image, while resembling a robot, has to give vent to his thoughts. In the hazy future run by computer-generated images, man will ultimately triumph, so the work suggests.

Quilang’s work pays homage to the artistic process, a slow and painstaking process of conjuring images. Though predominantly in pen and ink, with a leitmotif of undulating lines that seem to give birth to infinitesimal images, the work makes use of a paper guide, complete with captions visible on both sides of the frame.

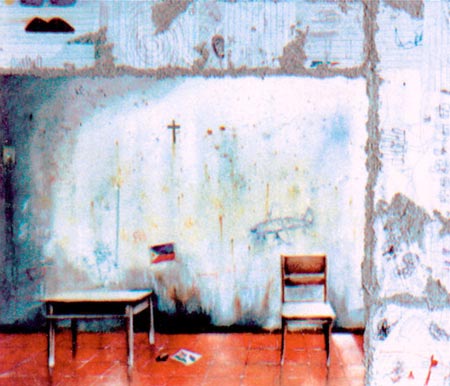

- Stellar, 2001 | Mixed Media, 38×32.5

Mixed bag

The Jurors’ Choice winners were a mixed bag. Lawrence Memije‘s “Stellar” makes us contemplate a child’s drawings and handwritings on the wall and on pad paper. Noli Manalang’s “Behind the Shadows” (in mixed media) is an illustrative diptych, a two-in-one portrait of a man and a woman, both physically challenged (she is blind while he is mute) and with inspiring quotations to make the message starkly clear. Panchoruelo Ibasco’s “Pandora’s Box” alludes to the chestful of surprises that pop out of life’s mysteries. Mark Mangugat’s “Expectation” resorts to the tried-and-tested image of a pregnant woman while Cecile Oliveros’ “Untitled” is a witty and disarming piece that celebrates the theme with the help of letters. Written on boxes, the complete text reads thus: “Each second you can be reborn. Each second there can be new beginnings. It is choice. It is your choice.”

There were, of course, other noteworthy entries that, for one reason or another, failed to make the grade. Ignored were two entries that yielded a firm hand in lifelike portraiture: Teodoro Penaflor’s “Our Hope” and Carlo Lizaran’s “Our Only Hope.” (Even the titles betray an imagination thinning out.) Similarly, the spirit of innovation by way of media (as in Rexell Livelo’s “Iba-ibang Mukha ng Pag-asa”), with its gallery of smiling faces, fell short of sheer expressivenes. Even a more belabored piece like “Power” by Henry Resales Jr., with its intricate mosaic of cut mirrors forming a giant chessboard, could not get the judges’ nod.

Perhaps, in hindsight, artists of whatever shade and stripe generally do not like to be hampered or limited by a highly explicit theme. Perhaps a more succinctly worded theme like “survival” and “peace” and “progress” would have sufficed and teased the imagination. That would have made a world of a difference.

Recent Comments